FOR FANS OF

African American fiction

Books about mermaids

Matriarchal societies

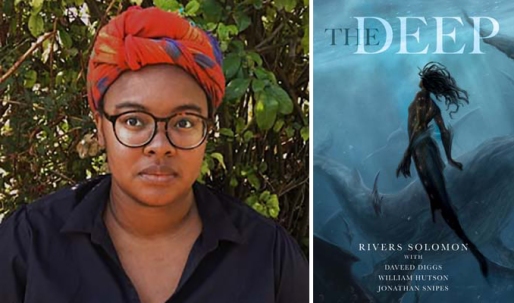

At 155 pages, Solomon’s THE DEEP is a fantastical dive into the pain of memory, strained relationships and aquatic self-harm that goes by much too quick. Yetu is our female protagonist and the historian of the wajinru people, an underwater tribe descended from the babies of women thrown off slave ships centuries ago. About five thousand strong, the wajinru can breathe in and out of the water and were originally rescued by whales, who they now honor as relatives.

The book begins as the wajinru are preparing for the Rememberance, the only time of the year Yetu is allowed to alleviate herself of the weight of her ancestors’ memories. Her people, most of whom worship her as a god, create a womb made of mud which protects them while Yetu shares the forgotten memories of their people and seizure-like fits take them over. Every other day of the year, Yetu battles with self-harm to cope. She presses her scales to lava vents to scorch away her nerves, she squeezes a dragonfish to death and uses its teeth to slice into her scales, and holds a shark tooth to her neck.

“Her people’s survival was reliant upon her suffering. It wasn’t the intention. It was no one’s wish. But it was her lot.”

For the Remembrance, Yetu is wrapped in fish skin and seaweed to “block out sensation” and make the Remembrance more bearable… at least it’s supposed to. During the procession, she seizes her opportunity to slip away, eventually finding herself washed ashore. Lucky for her, she meets a surface dweller named Oori, a stubborn fisherwoman who offers Yetu a daily catch, perhaps out of pitty. They slowly build a relationship by trading fish and seafaring advice. Over the course of several weeks, Yetu realizes how similar she and Oori’s struggles are. Oori is the last surviving member of her village and she doesn’t understand how Yetu could run away from her history when Oori would trade heaven and earth to get her people back.

There is a strong sense of feminine energy throughout the short novel, as well as some recurring themes. The constant influx of memories that Yetu suffers from could be a commentary about the weight African Americans feel when remembering a past stained with slavery and injustice. Memory becomes like another character, one that does not treat Yetu kindly. Also, themes of cultural identity become even more apparent when we see the opposite of Yetu emerge in Oori’s tragic story.

“Our mothers were pregnant two-legs thrown overboard while crossing the ocean on slave ships. We were born breathing water as we did in the womb. We built our home on the sea floor.”

Through their conversations, Oori realizes she must return to her homeland despite (and perhaps because of) her being the last survivor of her people. Yetu eventually realizes it is fear keeping her from returning to the stormy sea. Recognizing Oori’s strength, she knows it’s time to face the music.

Meanwhile, down below the surface, an uprising is happening. After an act of regicide, Yetu finally rides the tide back out to sea and returns to find half her population decimated. She succeeds in the unlikely endeavor of sharing her burden with all wajinru and welcomes Oori into her little corner of the ocean in a scene that’s both unexpected and pure magic.

“What does it mean to be born of the dead? What does it mean to begin?”

Happy reading 🙂